I had found myself enamored of clouds once already on this trip as I watched them stroll across the limitless expanses of sky in Argentine Patagonia. The open pampa revealed clouds as far as I could see. Like vast herds out on the plains, they floated in unison with the wind as their shepherd, driving them along as they grazed in their blue pasture.

In the Andes of Peru, the clouds were no longer benign, fluffy flocks. The roads almost never dropped under ten thousand feet in elevation and ushered me directly next to, on top of, and through the great white beasts I had admired from a distance in Patagonia. At times they slipped silently between the mountains like a platoon of soldiers through trees in a forest. Other times the road carried me around a curve or over a hill to suddenly find a cloud waiting for me, hanging motionless in the cold air between the peaks as though it were standing guard over them. Most days in Cusco as the afternoon storms rolled through you could hear the clouds speak in low growls and great guffaws of thunder.

These massive white and grey groundskeepers of the Andes were consistently maintaining and shaping the mountains, completely oblivious to the plans of humans. In many places there are large land murals or sculptures carved into the sides of mountains that overlook cities below. I suppose they embody human collective triumph since most of these murals tout the name of the city they stand over alongside Peru's national symbol. It seems appropriate then that the very highest peaks Andes have no murals or sculptures. Instead they are permanently dressed in ice and snow that comes, of course, from clouds.

The lower slopes also bear evidence of the clouds at work. In most of the country they are consistently covered in green leaves of every shape and size thanks to plentiful rain, which keeps markets full of things like mangoes, cherimoya, avocados, and a broader spectrum of spuds than Crayola could ever hope to put in a box. However the rains also wash out bridges and trigger landslides that do not discriminate between muddy footpaths or expertly-engineered, government-funded concrete highways. Even though our species is doing a better job than ever at undermining the natural systems that make life on this planet sustainable, the clouds in the Andes of Peru remain steadfast in their ambivalence to us. Despite evidence of centuries of human ingenuity and ambition throughout the mountains, this is still the clouds' kingdom.

Sunrise over Cusco

Part I: Cusco

If you have been to Machu Picchu, you have experienced greatness. Yet, like a truly great band who only ever gets credit for "that one song", the Inca are responsible for countless other wonders that most folks never hear about. Cusco, once the cosmological epicenter of all spiritual, cultural, economic, and military activity in South America's mightiest native empire, still retains undeniable traces of its former exalted status. Even the easily identified hallmarks that you can find in any other Latin American city have unique features that expose them as the "stand ins" for the originals in this city that was once (and in many ways still is) a native stronghold. The city's finest "colonial" structures, from historic government buildings to the most ornate cathedrals, stand upon still-exposed stone foundations designed and laid by native hands. On the hills overlooking the city, the famous Cristo Blanco is flanked by Saksaywaman and Q'enqo, sites whose significance outdates the big white Jesus by half a millennium.

Plaza de Armas

El Museo Inca and Qorikancha

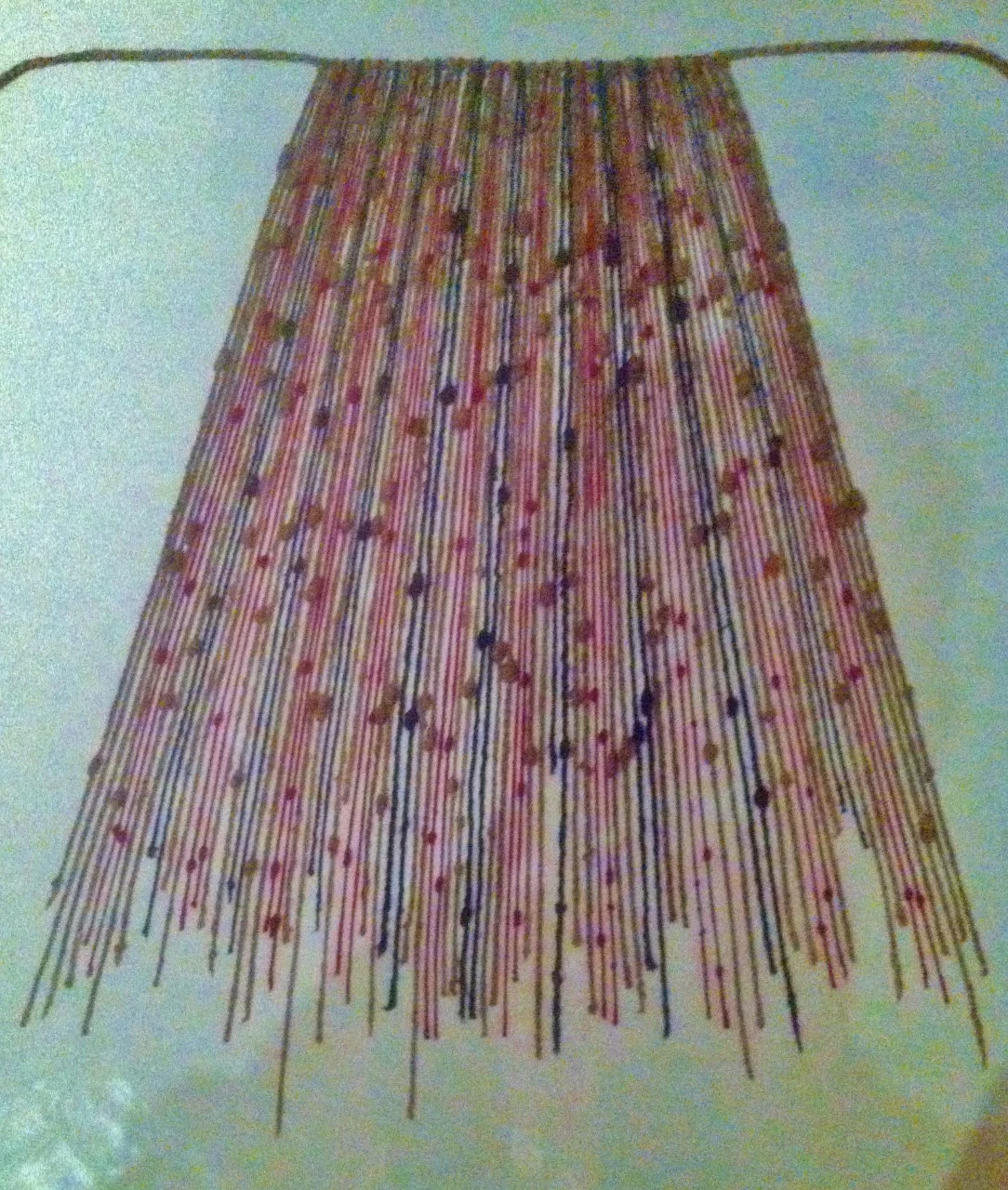

The Museo Inca...well it's a museum, so everything inside of it is about other things.

MY APOLOGIES IN ADVANCE FOR THE QUALITY. THE MUSEUM HAD ARMED GUARDS WHO WERE SERIOUSLY MEAN MUGGIN ANYONE CAUGHT WITH A CAMERA, SO I HAD TO USE MY PHONE

After the museum I strolled down to the Qorikancha. Once the site of the Cusco Temple of the Sun, the holiest site in the Inca Empire, it was toppled by the Spanish like most of the significant Incan structures in Cusco. Following the usual God, Gold, Glory playbook, they built a church directly on top of the old temple foundation (built, of course, by the Inca).

El Baratillo

One Saturday afternoon, Luis and Miguel, tour guides who work out of the hostel, took me down to the Baratillo. Given the name (derived from barato or "cheap") and its supposed nickname ("the smuggler's market). Miguel explained that most of the vendors at el Baratillo come from Bolivia on the weekend to sell their wares of dubious origin. Who could say no to that?

Unlike the San Pedro, this market was light on the alpaca sweaters and bracelets. In fact, El Baratillo was the first city attraction I visited where I did not see another obvious tourist (i.e. white person), and I soon found out why.

Beware inexperienced pickpockets

This picture, though not outstanding for its compositional merit, has a story behind it, all of which took place in about three or four seconds.

I was trying to capture a particularly crowded moment in the market as these men were moving furniture over their heads through the crowd. In the bustle I had fallen a few steps behind Luis and Miguel (ahead and to the right in the picture), when I felt an odd drizzle on the back of my head. I felt the back of my neck and what appeared to be something dry, like sand or corn meal, had been thrown on me. Instinctively I turned around and saw a man in the crowd staring excitedly at something in the distance. He looked at me and then pointed at something that was over my head and behind me. Without thinking I turned around to see what it was, though I was genuinely confused at how something that hit me on the back of the neck could have come from in front of me. (Keep in mind this was all in the span of a couple of seconds)

Suddenly, and again without thinking, something instinctual took over and I thrust my hands down toward my pockets, an instinct which I blame on watching too many heist movies and/or Travel Channel specials as a child. At any rate, I was surprised when I looked at my left hand and found I was grasping not my wallet, but a thin brown wrist. Attached to one end of this wrist was a hand that was clumsily grasping at my wallet through the fabric of my shorts. At the other end of the wrist was an arm and attached to that arm was a man who seemed to be looking off in a different direction. Amazingly the hand, as though acting on its own kleptomaniacal will, continued to paw at the outside of my pocket until I grasped the wrist harder and pulled it away. The man now turned to me, and I watched his mildly-confused expression immediately turn to surprise when his gaze met mine. In an instant he yanked himself from my hand slipped into the crowd. I turned to see if his partner, the pointing man, was still around, but he had apparently wised up before the butter-fingered pickpocket ran away. I stood there for just a moment before catching up to Luis and Miguel.

Cusco amistosa

As if the innate draw of Cusco weren't enough, crossing half the length of South America in less than a fortnight as well as frequent gas station strikes had left me in no hurry to continue the journey northward. I arrived at the tail-end of the "low season" for tourism in the city, which meant the hostel was nearly empty most nights, the markets were never too crowded, and I could easily enjoy ancient ruins all to myself. Best of all, the hostel staff (Yonatan, Sumner, Deisy, Jackie, and Alicia) as well as the owners, Nacho and Yesenia, were practically family by the time I left.

Yonatan was a twenty-two-year-old native Cusqueño who worked the night shift at the hostel reception. Nacho offered Yonatan a job after meeting him while Yonatan was working at his family's firewood business across the street from the hostel. Yonatan was incredibly friendly and did not hesitate to ask me for help with his English whenever he had a question. He later told me that during the tourist high-season he works as a guide, mainly on Inca Trail treks to Machu Picchu, so he wanted to polish his English as much as he could before the end of May.

On many occasions he invited me to hang out on his afternoons off. Most of the time he would show me sites as we walked around the city, but the trips almost always ended at a bar or a cafe where Yonatan was sure there would be some cute girls. One afternoon I was taking a break from the endless cycle of picture editing, blog writing, and bike repair and wandered across the street to chop wood with Yonatan for a while until it started to rain. After that afternoon Yonatan's dog, a shaggy blonde mutt who always had a bit of mud on her nose, would wander across the street to me and sheepishly roll over for a belly rub every time I walked outside the hostel door.

Nacho, the hostel owner, dressed more like he should be working at an advertising firm in the US than at a hostel in Perú. His affection for Americans' style was echoed in his car stereo presets Although he was a business owner with a wife, a toddler, and one more baby on the way, he was only in his late twenties and had the face of an even younger man.

In the course of my travels I have been fortunate enough to meet people who take my trip to heart even more than me, turning themselves into true champions for my odd cause. Nacho was one of those people. Any time I needed to make a run to the hardware store for bike maintenance or just wanted to go to the market for some dinner, Nacho insisted on driving me there and introducing me to some hole-in-the-wall bakery or ceviche joint on the way home. On other days, after spending the whole day on my back working on my bike or poring over the next blog entry to let people know I'm not dead, Nacho's wife, Yesenia, or the daytime manager, Deisy, would treat me to Peruvian home cooking.

Despite my initial discomfort at having my "adventure motorcyclist" status temporarily downgraded to "another tourist" in Cusco, I soon made enough appearances at neighborhood bodegas and the Pollo A La Brassa around the corner to at least be recognized as that white guy. Better yet, Nacho and Yesenia had no problem letting me turn one corner of the hostel lobby into a temporary garage to park and work on my bike.

When on the road for months at a time, any familiarity you can build up with locals, no matter how marginal, is gold. The discount or free drink that these microrelationships sometimes yield is always appreciated, but the truth is that even the most "lone wolf" traveler simply needs to feel some sense of camaraderie on occasion. Upon arriving in a new place, a thought often occurs to me (with great amazement and terror I might add) that literally hundreds or thousands of miles lay between myself and anyone who I can call a friend. While the exhilaration of being "out there" is what draws so many of us to adventures such as mine, in the end I get even more gratification from resetting the mileage counter to zero everywhere that I can.