Cañón del Pato spits me out where the Santa river delta empties into the Pacific Ocean. It's early afternoon when I get to Chimbote. The bike gets more gas and I get a bag of potato chips to hold me over until dinner.

On my way from Cusco I've heard that Chimbote and Trujillo, the next city on the road north, aren't recommended places for foreigners to stop for the night. Fortunately the highway runs straight and flat up the coast, so I'm soon cruising in fifth gear. This is the northernmost region of the same desert that runs all the way from central Chile. The foothills of the Andes lay grey and black on the horizon to my right, and sand dunes unfurl from the base of the mountains all the way to the ocean on my left. The open desert doesn't offer many opportunities to make a clandestine campsite, so I opt to stay indoors for the night. Later, while weaving the bike through clogged intersections in Chiclayo, an orange sun suggests that I call it a day.

The next morning I leave in a hurry and decide to follow the the Garmin stock map on my GPS. After all, there's only one highway running along Perú's coast, so how inaccurate could it be?

I should have known better. The pavement ends a few miles north of Chiclayo, but road on the screen continues in a direction that turns out to be a maze of rice paddies. After an hour of riding the narrow roads between paddies and ditches, I turn back for Chiclayo and find the right way toward Piura. I weave and honk my way between tuk-tuks, unintentionally cruising through colonial-style plazas filled with people, food, and live bands. Later I would find out that this was the third city founded by the Spanish in all of South America, and the first in Perú. I find a hostel, perform the now-familiar ritual of squeezing my bike through the front door, and sniff out a patio to enjoy dinner and a cold beer.

North of Piura the expanses of flat sand are punctuated more frequently with rocky hills. Even further north these hills dominate the landscape, with deep ravines running between them. Signs indicate that the area is a training ground for the Peruvian Air Force base in Talara, and I later learn that this land sits on top of Perú's largest oil reserve, which explains the military's interest in keeping this area secure (Perú fought several skirmshes and two territorial wars with Ecuador in the twentieth century).

An hour later the road twirls down from the desert hills and runs along the coast once more. I decide to stop in Máncora even though it's only mid-afternoon after remembering hearing Elise talk about the good beaches here. I don't have a swimsuit, but after a couple of months in the mountains I figure it can't hurt to park the bike for a few days and get sunburnt.

Up until this point my mingling with backpackers has been minimal. For the most part this was circumstantial, since the roads I enjoy riding are mostly inaccessible by bus, not to mention the fact that partying in a backpacker hostel every night isn't conducive to an enjoyable ride the next day. Since I'll be parking the bike for a while, I decide to check out a particular hostel I had heard of through a few friends, but I really didn't know what I was getting in to. This chain of hostels (which I won't name here but you can contact me directly if you really want to know) spans throughout South America, offering a non-stop party to those with the money, time, and brain cells to spare. Take the addition of the beach in Máncora, and you have what I would describe to my American readers as a 24/7/365 Spring Break.

After a couple of days in a place like this, a stratification takes place that separates the patrons according to their capacity for ceaseless inebriation. Something tells me I should consider moving on soon. Perhaps it's my age, or the fact that I'm not single, or maybe it's how scared I get when I find out how many of the bartenders came to the hostel as patrons and are still working off their tabs several months later. Whatever it is, I find myself in the group that feels like this was fun the first couple of days but now we just want to read or chat over a few beers

While the insanity continues at the bar, you can find us by the hammocks; Nick, an Aussie with a penchant for good books and surfing; Jakob, a Swede with honorary Australian citizenship who might've been mistaken for Jesus; Carina, a beautiful German who was actually a salty sea dawg by trade; Adam and Lisa, a English couple who never fail to be the life of the party and whose kindness and charisma have no end. Later we add Steve, Andy, and Mike--from Scotland, England, and Colorado, respectively--to our ranks. Even though we've only spent a few days together, we get along so exceptionally well that, once again, I have a hard time convincing myself to say goodbye to my new friends and keep moving along. When the day comes to leave it takes almost no convincing for me to agree to extend my stay in Perú just a little while longer (of course it doesn't hurt that I've already overstayed my traveler's visa by nearly a month). Nick wants to check out the surf in Lobitos, some tiny town about an hour south of Máncora. I recall a small sign on the side of the desert highway on my way up from Piura that pointed to a sandy trail leading into the desert.

Later that afternoon I find the dusty brown sign next to the highway that reads "LOBITOS" with an arrow pointing down that same dusty path among the cacti and rocks. Every few kilometers is marked by an army checkpoint where I'm asked to explain why I'm riding through an active oil field, each one costing me a few minutes of now-dwindling sunlight. Trails branch off in all directions toward pumps scattered throughout the desert, and I try my hardest to remember the guards' directions.

I've lost the sun completely by the time I roll on to pavement again, eventually arriving into a town I assume to be Lobitos by following the only lights in sight. My friends took the bus from Máncora, but there's no bus station here. I pull up to a house whose owner, known by locals as Señor Tranqui, runs a restaurant on the front porch. A while later a few locals ride three-up on a small dirtbike and park in front of Tranqui's place. We soon get to talking and I explain that I'm waiting on my friends, although I've been waiting a couple of hours at this point. One of them--a guy named Eduardo who I notice is riding without shoes, just a hoodie and board shorts--offers to let me crash at his place, assuring me that Lobitos is small enough to find my friends in the morning.

I follow Eduardo and his two passengers through the dark as he drops them off, and we continue past the outskirts of town, where the pavement gives way to sandy roads. In my mirrors I can see the distinct line where the streetlights stop on the edge of town, but soon we come to a group of small bungalows on sandy hills overlooking the beach. When we reach Eduardo's place, he warns me to watch where I step while he gingerly hop-skotches his way around the unlit yard. With my flashlight I see why; strewn on the ground around the house are nails, rocks, bamboo planks, tools, and piles of unmixed concrete. I can hear Eduardo up ahead in the dark, telling me about how he settled in Lobitos permanently after traveling around South America in search of the best surf spots. I stumble up the small hill and find myself standing on a concrete slab, about twenty feet by ten, with two-and-a-half walls surrounding it and a thatched bamboo roof overhead. The house is a work in progress, which Eduardo clarifies to mean that he works on it on the rare occasion that the waves are too low to surf. I would realize over the next few days that almost all work schedules in Lobitos are determined by the quality of the surf.

Eduardo's incomplete house not only speaks to his priorities, but also to the climate and people of Lobitos. The coastal desert of Perú, like that of Chile, sees almost no rainfall for years on end, except for the so called "El Niño" events, when warm ocean currents bring monsoon-like rainstorms to northern Perú. The events are so extreme that the locals talk about it like a person, and the last major El Niño in 1998 brought such severe flooding to this desert that changed the geography of the beaches in Lobitos and created three sublimely surfable waves. Still, Lobitos remains a unknown backwater outside of the surf world, so a stroll through town with a local was filled with numerous stops to chat with shop owners or whoever happened to be walking down the street. Eduardo thinks nothing of leaving his clothes, computer, surfboards, and surf photography equipment (which I can assure you is not cheap stuff) in his open beach shack whenever he leaves.

Piscinas, Lobitos' biggest wave. Don't get smashed on the rocks

Even seen a Peruvian Hairless Dog?

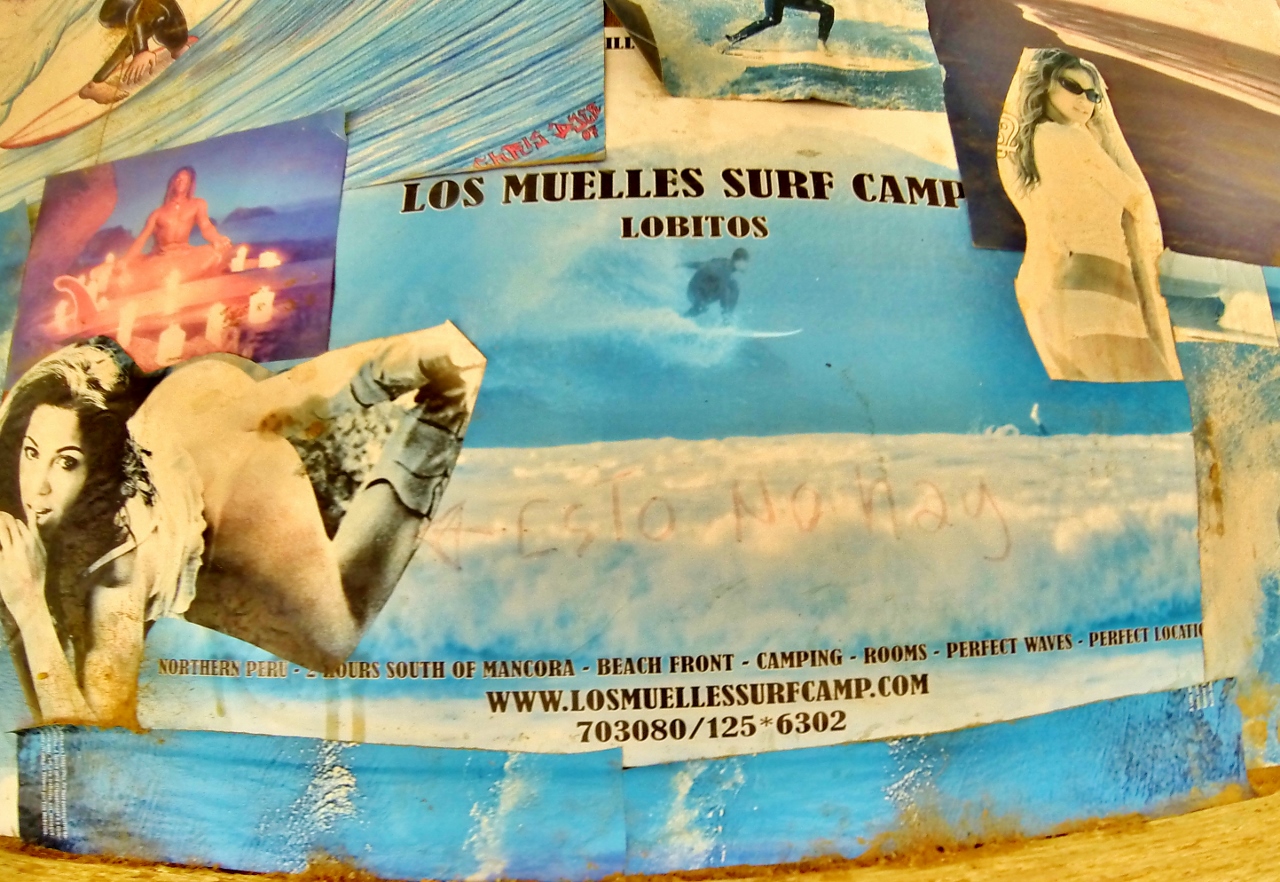

Thus I was convinced really get to know what Lobitos was all about. The next morning I meet Carlos and Jhonny, who converted an old military warehouse into the Surf Camp, a hostel right on the beach especially for surfers. Turns out they're also fans of dual-sport bikes, and showed me their two Transalps that they bought off a couple of Swiss tourists earlier this year.

I also recover my friends, who had to take a late night tuk-tuk to town after realizing the bus only goes as far as Talara. We reconvene at a hostel called La Casona, an old mansion perched on a beachside bluff. The hostel staff are much more concerned with getting their daily surf fix than working the front desk or the kitchen, whose daily specials are nevertheless proudly advertised by the front door of the hostel. We stay, of course, because there's no other hostel in town big enough for the nine of us.

After talking about it with some of Eduardo's friends and noting the regularity with which they head out to the beach, it becomes apparent that surfing, or as the locals say correr tabla ("run board"), transcends recreation in Lobitos, dwelling nearer to the level of religious ritual. It even has its pilgrims, believers in the power of waves who come to Lobitos from every corner of the earth with boards in hand. There are also the surf sages and oracles who all found Lobitos and decided to devote themselves entirely to this temple, like Eduardo and Carlos, both native limeños, or the Argentinean staff members from La Casona.

Stay in Lobitos for more than a day, and you're bound to succumb to the call of the waves yourself (if not out of interest than out of sheer lack of much else to do). Nick gives me some pointers before I head out, and desping receiving a beating and many mouthfuls of briny Pacific Punch, I manage to stand up a few times. Nick busted his board in Máncora and has to deal with a chest cold for the first few days that we're in Lobitos, but by the end of the week I help him patch up his board and he shows us how it's done.

In spite of the surfing, Lobitos is first and foremost an oil town. Almost a century before El Niño turned its beaches into a surfer's sanctuary, the town was settled by a British oil company, who built the town for its employees' families. For a time the town was a peculiar jewel in the empty coastal desert, housing hundreds of American and British employees' families in English-style houses. In no time Lobitos became a boom town, boasting visits from English royalty, a three-story casino, and the first movie theater in South America. Six decades later, at the height of the Cold War, the Peruvian military seized control of the country and nationalized the Lobitos oil field, and within a week the foreign oil companies and their employees vacated the town. The Nixon administration, with the compliance of the British government, was happy to recognize the emergence of another right-wing junta, and quickly negotiated a payout for the rights to Lobitos.

Over the next fifty years, most of Lobitos' buildings and infrastructure were dismantled and sold by the military government, while the rest was left to deteriorate. Today, most original structures are gone (like the movie theater) or in utter dilapidation (like the casino with its caved-in roof), but a few have been maintained through the years, sustained by the small population of Peruvian oil workers who moved in after the 1968 coup left Lobitos a ghost town. Large warehouses, formerly used by the military, now serve as restaurants and hostels. On the southern edge of town, Eduardo is among dozens of new residents who are building beachside houses, restaurants, and hotels in anticipation of another Lobitos boom.

Due to its peculiar condition, having fun in Lobitos as a non-surfer is a creative exercise in itself. A few days into our stay, Andy gets the itch to venture out to one of the oil platforms that dot the bay. We all venture down to the dock with a wad of cash and find a fisherman with a boat big enough to take all of us out there.

L to R: Andy, Carina, Nick, Lisa, Fisherman, Jakob (red shirt), Mike, Rosie (from Germany), and Daniel (from Massachusetts)

If diving off of rusty steel towers ain't your thing, you can ask locals how to get to the seaside Capullanas caves. One end of this small cave system opens up to a small beach, hemmed in by sandstone cliffs dotted with the nests of Blue-footed Boobies.

What I admire more than anything about the people here is an overwhelming sense of satisfaction with their lives in the type of place that most other people would dismiss as bleak and hopeless. Whether it's abandoning the hostel desk to take advantage of an unexpected swell or the entire town turning out on a Sunday night for the women's rec-league soccer championship, folks in Lobitos take joy in what life offers them. In another life I imagine I may just stay in Lobitos forever, riding my own bike around town with no shoes on, waiting around at El Tranqui until someone gets word that the surf's up. In a desert this close to the equator, the only season is warm and dry, and Eduardo tells me that Lobitos has a surfable wave more than three hundred days a year, as predictably agreeable as the people.

Of course, things won't stay the same forever. This town has felt the forces of nature and politics before, and both seem poised to deal a new hand to Lobitos. A rare rainstorm passes through one night, bringing talk of El Niño all around town. Most folks are certain "the child" will return this year, and one of Eduardo's friends is already moving his house further away from the beach to avoid getting washed away. In Lima, the Pro Inversión Project, a plan to auction off the small military base on Lobitos' north shore to private resort developers, will be taking bids in the coming weeks. Some people in town view it with optimism, but I tend to side with those who don't want to see Lobitos become another Máncora, where it's easier to find someone to sell you coke than it is to find someone like Eduardo, who will invite you to his house and watch surf videos instead.

The same afternoon that I take pictures of Nick, I turn around from the beach and notice the ragged skyline of Lobitos; the rusty fisherman's dock, collapsed edifices of old Lobitos, La Casona, myriad straw-roof shacks on the new side of town, and an empty beach save for a handful of surfers. It seems important to take a picture of this, to make a plot on the chart of Lobitos' historical trajectory, even if I don't know which direction it's headed. I only know that it will change.

Lobitos, Talara, Perú. April 30, 2014. I wonder what this will look like five, ten, or fifty years from now