This post contains a lot of pictures and gifs, but IN ORDER TO KEEP LOADTIME to a minimum i was unable to include all that i have. if you'd like to see more, i've uploaded many more pictures and gifs of zoorefugio tarqui's animals in a separate gallery. click here to view them.

PART II: ZOOREFUGIO TARQUI

Riding across Ecuador gets me thinking of the countless times I've crossed Texas, my home state that is two-and-a-half times the size of this entire country. Admittedly, Texas' scenic pickings--strewn out over hundreds miles of monotonous landscape and truck rest stops--are paltry compared to this country.

Ecuatorianos take pride in the staggering geographical diversity that their small country offers. Thanks to a young and well-maintained national network of highways, you can start your day in the dry forests of the western coast and drive up into the cloud forests and high grassy valleys of the Andes in only a few hours. Quito, perched just shy of 10,000 feet, sits another couple of hours away from the first palms, chontillas, and zapote trees that form the edge of the Amazon rainforest east of the mountains.

My destination is the Zoorefugio Tarqui, whose namesake is a small village just south of Puyo, the capital of Pastaza province. The land here is an uninterrupted carpet of green that bunches up on the foothills of the Andes in the west and unfurls east all the way to to the Peruvian border. While awaiting bike repairs in Quito I used Helpx.net to get in touch with Fanny Bonilla, the co-owner of the Zoorefugio Tarqui. They accept international volunteers at the park throughout the year, and Fanny is more than happy to have another helping hand on the way since most volunteers return to their home countries at the end of the summer. There's a volunteer house on the zoo grounds that houses two dozen, and earlier this year Fanny's husband, William, even had to rent extra rooms in a neighbor's house to accommodate the surplus of volunteers. By the time I arrive all but two volunteers have gone, but there are still animals to feed and a park to keep clean, which means no time for anyone to hold my hand for the "training" portion of my stint at the park. Not an hour after my arrival, they put me to work right away holding a sick Boa Constrictor for injections.

For the majority of my tour of duty as a Zoorefugio Tarqui volunteer, I am joined by two Spaniards and two Danes. Agustín, jokingly known as "el Tiburón", comes from Barcelona and has already spent a couple months at the park and another Spanish volunteer, a veterinarian named Maria, is wrapping up her stint at Tarqui before returning to her full-time job at a wildlife center in Perú. Kristina and Tore, a Danish couple, have come as part of their studies to become professional zookeepers (I did not know this before I met them either but yes, you really can go to school to become a zookeeper in Denmark). In the past few years they have worked at wildlife centers around Europe and in places such as California, Bolivia, and Cameroon.

Compared to the others, it's clear that I have relatively little to bring to the table in terms of experience. Luckily I can provide a more vital service than just cleaning cages and cutting up fruit for the animals; it turns out the Danes can speak many languages, but Spanish is not yet one of them. Fanny is the only one among zoo staff and volunteers who can speak English, but she's too busy to translate between the volunteers all day long. Now I understand why Fanny was eager to have me around to help translate for Tore and Kristina while we work.

In addition to volunteer power, Zoorefugio Tarqui also runs on the devotion of William's family. If Fanny is the brains, the heart of Zoorefugio Tarqui belongs to William López. A lifetime spent in the rainforest, walking in the shade of its trees and fishing in its rivers, has given William a passion for the animals of this incredible place. Conviction is the only way to explain why William, a contract electrician, started Zoorefugio Tarqui without any formal training with animals or zookeeping.

Most days, though, you can find William and Fanny running the restaurant at the zoo's front gate. As it's name implies, La Choza (The Hut) is in fact a big thatched-roof hut. Fanny keeps La Choza in tune and on time like an orchestra conductor, while William works the grill as masterfully as any concert pianist, sending smoky notes of steak, chicken, and freshly-caught fish sailing about the restaurant. Their kids--Jenny, Amy, and José--make themselves busy around the restaurant or the park.

Fifi, chairwoman of Zoorefugio Tarqui's customer relations department, takes a nap in front of La Choza

As its name implies, Zoorefugio Tarqui is not a typical zoo. William and Fanny adhere to a strict policy of rescue and rehabilitation, and the well-being of the animals in their care is paramount. Ecuador's government stands near the top of the world's list in terms of environmental protection, and subsidies provide support for countless ecological reserves, wildlife refuges, and rehabilitation centers. Each year the government also seizes thousands of animals from the black market with priority placed on returning as many as possible to the wild. Unfortunately, many animals grow accustomed to humans while in captivity, or are injured by hunters or trappers, leaving them unable to fend for themselves back in the jungle. The Ecuadorian government is less forthcoming with financial support for these animals, so it is easy for them to end up back on the black market. William and Fanny decided make them the focus of Zoorefugio Tarqui to keep them out of the illegal pet trade for good.

Birds

As of February 2015, Zoorefugio Tarqui has completed several new enclosures for their birds. You can see the updates on their facebook page: facebook.com/zoorefugiotarqui.

Over fifty specimens from eight different species make up the bulk of Zoorefugio Tarqui's animal roster, including seven different parrot species. The most numerous are the Blue-headed Parrots ("Loro cabeciazul"), and Zoorefugio Tarqui actually has a very successful breeding program in place for these chatty creatures. Along with the Red-masked Parakeets, Orange-winged Amazons and Mealy Amazons, the Blue-heads make up the park's loudest corner by far. From sunup to sundown their alarm-like squawks and shrieks, evolved for the purpose of piercing the dense rainforest canopy, make the parrots impossible to ignore. However, parrots' incredible intelligence is no secret, and thousands of guests over the years have exploited that intelligence by teaching them words and phrases in Spanish which the birds recite quite convincingly. Several times while doing chores around the park, I find myself trying to eavesdrop on conversations I can hear in the distance, uncertain if the occasional words I pick out are part of an actual conversation or just parrot chatter.

Next door live their larger, even more colorful cousins: macaws. At the time of my visit, Zoorefugio Tarqui has a handful of macaws, including Scarlet, with their robust red bodies and rainbow-tipped wings, Blue-and-yellow, and Chestnut-fronted macaws. Most of the macaws at Zoorefugio Tarqui were illegally trapped and kept as pets, and the incidental manner of their arrival means there is only one male in the entire group. These sensitive birds prefer living and feeding in the highest trees of the forest, so I'm glad I get to help set the concrete pillars for their soon-to-be thirty-foot tall enclosure that should let them stretch their wings.

Though I enjoy seeing them more in the wild, it's easy to see why so many people keep these highly-intelligent birds as pets. Within a few days, one of the ladies has taken a shining to me. She's a gorgeous Blue-and-yellow with brilliant feathers from her head to her rump. Her tailfeathers, however, are all tattered or missing. I come to find out that when she arrived earlier in the year, her entire body looked just as scraggly--the result of poor treatment and stress while being kept as a pet before she was taken into government custody. Every time I pass the macaw enclosure I see her perched against the front of the cage to greet me with a modest squawk, and I realize she must be keeping an eye out for me. After that, I make sure to always keep an extra bit of fruit in my pocket so I don't disappoint my admirer.

The parrots feed twice a day on a variety of fresh fruits, seeds, and nuts. The parrots' next door neighbors have a different appetite. Zoorefugio Tarqui's resident raptors are two White Hawks. Unlike the noisy and amicable parrots, these subtle carnivores silently watch with keen eyes from their perches high in the cage. When it comes time to feed, they enjoy a menu of fresh fish, raw chicken and steak, and the occasional live guinea pig or quail chick.

Reptiles

At the time of my visit the two Boa Constrictors eagerly await their new exhibit at the southwest corner of the park. A third boa, dropped off by firefighters who found it on the road a few weeks before, inhabits a cage in the vet clinic. Unlike the other snakes, who were raised as pets, this wild snake doesn't take so well to human contact. It spends most of its time hissing at staff that wander too close to the cage. We arrange to release it at a remote wildlife refuge located on the slopes of the mountains to the west.

When the cage is completed, the two snakes are introduced to their new home and given a housewarming gift of three guinea pigs to help them get settled in.

Three species of Caiman also call Zoorefugio Tarqui home. A handful of Smooth-fronted Caiman, each one ranging from three to five feet in length (roughly one to two meters) enjoy their own pond, while the larger species--two Black Caiman and one Spectacled Caiman--reside in another. The park's lowest-maintenance residents, Caiman split their time floating in the water and sunbathing on the shore, and even share their ponds with small turtles and fish. Interestingly, the staff doesn't actually feed the Caiman. Instead, we toss fish and turtle food into the pond. The Caiman eagerly await their feeding time, taking advantage of the frenzy of fish and turtles at the water's surface to snatch a live meal for themselves. They can not return to the wild due to injuries from hunters' traps, but this system of feeding encourages them to maintain their hunting instincts and skills.

The park's most relaxed residents, Yellow-footed Tortoises, number about thirty. Their enclosure features a tunnel and a long narrow strip along the perimeter of the Black Caiman pond and the Capuchin Monkey cage, making for a great tortoise race track. Despite being the slowest animals on site, they are the most successful escape artists at the park, so the staff always has to keep an eye our for tortoises that manage to break into the Caiman pond. Amazingly, no one ever manages to catch them doing this. Their perplexing escape trick remains a mystery to this day.

Mammals

Upon entry to Zoorefugio Tarqui, the visitors are greeted by Julieta and Spidey, a pair of Spider Monkeys. Spidey serves as one of the best testimonies of Zoorefugio Tarqui's mission; he lost a hand and his tail to a hunter's trap when he was only a baby. Spider Monkeys spend almost their entire lives in the trees, swinging from branch to branch using their hands, feet, and tails, so Spidey's injuries were utterly debilitating. Fortunately he was rescued and taken care of at a nearby wildlife center until he came to Zoorefugio Tarqui so he could be with another one of his species. Nowadays, thanks to the zoo staff's great treatment and his own resilience, Spidey dazzles park visitors with his one-armed acrobatics. I find myself completely enthralled to watch him maneuver around the branches and ropes that hang high off the ground in his cage. Despite the many hours I spend watching, I never see him slip once.

Julieta the Spider Monkey

Just beyond the Spider Monkey enclosure, two separate packs of Capuchin Monkeys, twenty-one in all, reside in two different cages. Capuchins are very intelligent and not afraid to interact with park visitors or other animals who wander within grasp of the cage. In order to keep the monkeys out of range of park visitors--or, more accurately, to keep visitors out of range of the monkeys--the tortoise pit between the visitor path and the Capuchin cage serves as a low-metabolism moat. Now and then some poor tortoise gets a noogie from one of the monkeys if he wanders too close to the cage. Other monkeys climb to the top of the cage and drop rocks and sticks through the fence and on to unsuspecting tortoises below. Luckily they bounce right off the tortoise's shells, and it seems that the tortoises are either too patient or unintelligent to be fazed by the bullying.

Capuchins live their life according to a strict group hierarchy with a dominant alpha male at the top. Each group's pecking order is so strictly enforced that alpha males will viciously defend their group from any outsiders that pose a potential threat to their dominance. Only those who gradually gain the trust of the alpha male can safely interact with the Capuchins. If anyone rubs the alpha male the wrong way, he can call on the rest of the group to swarm the unwanted intruder. Over time Capuchin attacks have left nearly all the zoo staff in genuine fear of entering the monkeys' cage for cleaning or feeding.

Agustín is in charge of the monkey exhibits and asks if I'd like to try to get in with the Capuchins' club. Based on what others tell me about these monkeys, I'm not sure if he is asking me as a joke or out of desperation since nobody else is willing to do any work in the monkey cage. He points out Jacky, the dominant male whose oversized fangs help me understand how such a small animal could strike fear in a human. According to Agustín, the key is humiliation and generosity, and over the course of a few days I frequently visit the Capuchin enclosure to pass pieces of papaya to Jacky through the cage, never looking him in the eye and resisting the urge to smile; Capuchins and most other monkeys take bare teeth as a threat. Once Jacky is comfortable with me hanging around his group, it's time to enter the cage. As a final step to ingratiate myself with the whole group, Agustín hands me the food bucket as we enter the cage. I carefully approach Jacky, whose inch-long fangs hang out over his top lip, and slowly raise the bucket to the branch where he is sitting. Jacky picks out a grape, tucks a corn cobb under each foot to snack on later, and starts to eat. My patience has paid off, and Jacky has accepted me as an honorary Capuchin Monkey. Now that the big man has given his approval, in seconds monkeys leaping from every direction on to my head, shoulders, arms, and climbing up my legs to check me out and pick out fruit from my bucket.

Even if they weren't fond of attacking people, the Capuchins still couldn't claim the title of Cutest Monkey at Zoorefugio Tarqui. For that, you have to go to the southwest corner of the park until you reach a seemingly-empty cage. It may take a few moments, but patient and quiet visitors will notice a stirring in the dense waist-high grass. Then, a tiny brown and black hairball zips out of the grass and into sight, leaping from branch to branch and bouncing off the walls of the enclosure. Once you get to know him, Zoorefugio's lone male Saddleback Tamarin is one of their most photogenic residents.

Zoorefugio Tarqui also has two unofficial monkey residents; a pair of wild Squirrel Monkeys who live in the trees around the park. With few predators and ample opportunities to steal fresh fruit from the zoo staff, these little guys are anything but shy around humans. After slipping her a bit of banana just once, I'm never able to sneak through the east wing of the zoo without my new "friend" dropping from a branch overhead on to my shoulders so she can beg for another handout.

The bird and monkey enclosures of the zoo's east wing end sit under a thick green canopy of tall leafy trees. The southwest side features broad, flat enclosures with plenty of grass, puddles, and mudpits that put some of the zoo's largest residents right at home. The most numerous are the Peccaries, better known as javelinas where I come from. These wild pigs have thick, bristly fur and big tusks with a bad attitude to match, making them far more intimidating then their pink farmyard cousins. The zoo has two species; the Collared Peccary and the White-lipped Peccary, which can be found in the wild from the southern United States all the way down to Argentina.

Originally, only a handful of pigs arrived at Zoorefugio Tarqui, but anyone who knows wild pigs will tell you that their fertility rivals that of rabbits. The group here now numbers nearly forty. In addition to fresh corn, herbs, and bananas, they help dispose of the slop from the zoo's restaurant.

White-lipped Peccary

Next door, the zoo's largest enclosure boasts more than an acre of delicious leafy plants and a pair of ponds, making this exhibit an herbivore's paradise. Capybaras are the world's largest rodent and shockingly adept swimmers. They spend their afternoons paddling around in the water, unburdened by the threat of a sudden caiman or jaguar attack that they would face in the wild. A trio of Tapirs make up a family; a male named Bambi, a female named Rose, and their young baby. Silvia takes after shy Rose, and rarely leaves her mother's side, though her gregarious father has no fear of humans. As Bambi wanders around the enclosure's fenceline greeting park visitors, he and Rose keep in touch long distance with a surprisingly dulcet and high-pitched song that you would never expect to hear from an animal that weighs over four-hundred pounds.

The southwest end of the park also features a fine collection of species best described as "critters"--or "varmints", if you prefer--by those of us from the southern United States. A pair of Crab-eating Raccoons, with a leaner build and a thinner, browner coat than their North American cousins, live in one of the newest enclosures at the park. Tore and Kristina have grown particularly fond of them, and they undertake several habitat enrichment projects for these intelligent, mask-wearing cuties. The Danes tell me that the raccoons go crazy for huge purple-shelled snails that creep around in shady spots of the park path, so I make sure to collect a couple of snails every day so I can watch the raccoons furiously smash open the shells and enjoy the succulent reward within. Pure ecstasy is the face of a raccoon with a muzzle covered in snail juice and bits of shell.

Around the corner from the raccoons live their relatives, the Ring-tailed Coatis. These highly active squeakers bear a close resemblance to the raccoons, with the only difference being their long narrow snouts and more distinguished rings of alternating color on their tails.

The other two species of the critter corner are the Greater Grison and a family of Tayras. Both of these cat-sized species are closely related to weasels and ferrets, making them highly active hunters and climbers. Willy, the Grison, affectionately named after the park's owner. He is more docile than his neighbors, the Tayras, but when it comes time to feed on live quail chicks Willy puts his hunting prowess on display. He's generally quite tame, but his coat makes him look exactly like a Honey Badger, which is reason enough to keep my fingers out of reach of Willy's curious snout and claws whenever I clean his cage.

Next door to Willy live the Tayras, known locally as "Cabeza de Mate". Their temperament is probably best described as somewhere between a killer bee and Satan's cat. They spend their days leaping among branches and climbing the chainlink walls of their enclosure, snarling at any visitors that wander too close. To support all this activity, the adults can eat half their body weight in fruit and meat every day.

The pair of Tayras have a reason for their lack of hospitality; they have to protect their vulnerable three-week-old kit. "Devoted parents" doesn't begin to describe the dedication these two have to their baby. I wonder if the pair might behave themselves a bit more peacefully if there weren't a kit to care for. One day, while watching the Tayras snarl and claw at us through the chain-link, Tore recalls the time a Tayra escaped from its cage at a zoo he was working at in Bolivia. They managed to catch it, but not before it had slaughtered a group of Coatis in a nearby enclosure. After this, when asked by visitors if I'm afraid of any of the animals at the zoo getting loose, I tell them to forget the jaguars, pumas, or caimans; if any animal at Zoorefugio Tarqui should be feared, it's the Tayras.

Undoubtedly, the fan favorites of Zoorefugio Tarqui are the cats. On the smaller end are the bobcat-sized Ocelots and a single Margay, an animal which I had never heard of before working at the park. This housecat-sized feline has a spotted coat like its larger Ocelot and Jaguar cousins, as well as massive claws fit for hunting prey high in the rainforest canopy.

One morning I get to learn about these claws personally when it comes time to check the rain-collection tanks at the top of the zoo's the water tower. The base of the tower also serves as the Margay's enclosure, and anyone wanting to climb the tower must climb over the cage first. From inside his small wooden house, the Margay stares as I scramble up the chainlink on the side of his cage. I keep one nervous eye on the opening of his small house the whole time, though all I can see are two enormous eyes and the occasional twitch of a whisker.

After checking the water tanks and snapping a few pictures, I climb down the side of the tower and ease my way back across the beams on the roof of the Margay's cage. This time when I arrive at the edge of the cage I find the same huge eyes and whiskers waiting for me, along with the rest of this pint-sized killer. He seems only slightly interested as I cautiously begin lowering myself down the side of the chainlink, and I mistake his playful curiosity for tameness. Suddenly he sticks a paw through the cage, batting at my hand in an attempt to play. Unfortunately when a Margay wants to play he uses same long claws that can snatch birds and monkeys in the wild. I let out a yelp and jump back on top of the cage, out of reach of my unwanted playmate. He continues to playfully poke his paws through the cage each time I try to climb down. The tiny psycho keeps me trapped on top of the cage for almost ten minutes, much to the delight of park visitors walking by, before I make a final desperate attempt to climb down the chainlink. Once again he pokes my finger, triggering my reflex to let go of the fence and sending me to the ground with a thud.

A family of Pumas live in two big enclosures atop the hill at the park's center. Pumas, also called Cougars or Mountain Lions in the U.S., have successfully colonized all of the Americas, from Canada to Patagonia, giving them them the largest range of any wild feline.

Shakira and Ranger, the mother and father, have successfully conceived and raised a family at Zoorefugio Tarqui. While the cubs natural instincts keeps them somewhat wary of humans, their parents--especially Shakira-- remain very tame due to their upbringing as household pets. Shakira readily rubs up against the side of her cage whenever I visit. Soon I realize this is her way of asking for a scratch behind the ear. After a lifetime watching wild Pumas hunt in nature shows and being warned about them in the wild, it's amazing to now have one begging me to pet her.

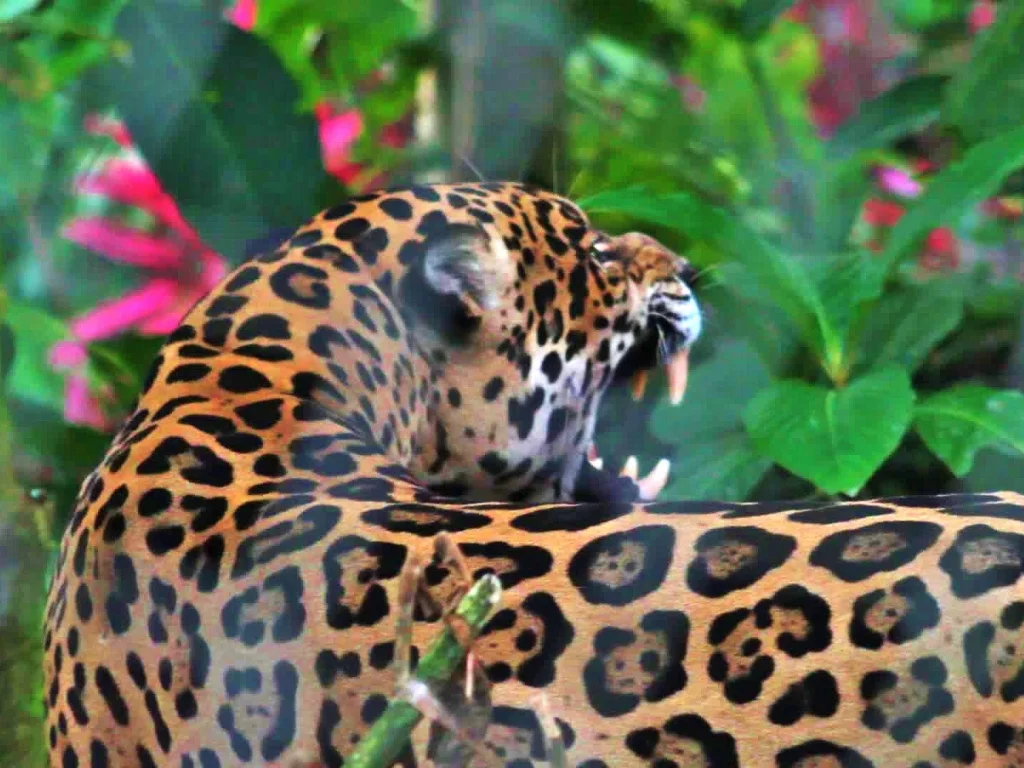

My favorite felines, and the favorites of most of the park's visitors, live in two separate enclosures next to the Puma family. Two adult Jaguars, Precioso and Brenda, rarely disappoint the crowds that they draw thanks to their highly active lifestyles. Most other big cat species spend the majority of the daytime sleeping, but Jaguars spend about half of their day on the move. Zoorefugio Tarqui's Jaguars give visitors plenty of sighting opportunities as they wander around their huge enclosures.

Brenda, the female Jaguar, arrived at Tarqui a few years ago after spending most of her life at another wildlife center. As the older of the two Jaguars, she takes things at a more relaxed pace and can usually be found greeting park visitors from her favorite treehouse perch.

Brenda the Jaguar

Precioso, the younger male, has spent nearly his entire life at Tarqui. William tells me that seven years ago some local farmers had planned on killing a Jaguar cub they had found in order to keep him from growing into another threat to their livestock. Jaguars are the apex predator of the Amazon thanks in part to their incredibly powerful bite. Relative to their size, Jaguars have the strongest jaws of any feline, which they use to crush their prey's skull. Cattle and other livestock stand little chance against a hungry Jaguar, so it's easy to see why the farmers wanted to kill the cub.

Fortunately someone convinced the farmers to give up the young Jaguar, and so William and Fanny adopted the tiny cub and called him Precioso. Nowadays he is the king of Zoorefugio Tarqui, weighing over 200 pounds (nearly 100 kilograms). Throughout the day you can hear parrot squawks and monkey chatter punctuated by his thunderous bellows, groundshaking growls, and roars that rumble across the park. Despite his grumbling, Precioso is actually very curious and playful once you earn his trust. Of course, peek-a-boo with a Jaguar can still very easily cost you a few fingers if you aren't careful.

Unlike Shakira and Ranger, Zoorefugio Tarqui's Jaguars have a tense relationship. Wild Jaguars prefer solitary lives, and even in captivity the young Precioso very much values his bachelor status. A few attempts have been made to get the Jaguars to mate, but so far they have only produced lots of growls and hisses.

The animals of Zoorefugio Tarqui represent one of the most important ecosystems in the world. As most people know, it is also one of the most threatened. William's family and the volunteers that come to Ecuador from all over the world give up their time and money to care for these animals with the hope that visitors might see them as an extension of the rainforest they call home. Enterprises such as Zoorefugio Tarqui--those that take the environment and social responsibility into account when making business decisions--often face difficulties when forced to monetize things that you truly can not put a price on. I had my own reservations about working at a zoo prior to coming to Tarqui, especially the possibility of facing a choice between what is "good for the bottom line" and an animal's true well-being. After a month with William's family and the volunteers at Zoorefugio Tarqui, I could not be more certain of their passion and their willingness to make sacrifices in their own lives for the better of the animals.

Unlike many other zoos and wildlife centers in Ecuador, Zoorefugio Tarqui does not accept any money from the Ecuadorian government and they never buy or sell animals. William and Fanny know that this means missing out on lots of potential cash for the growing demands of the animals, but they believe even more in preserving their ability to do whatever they feel is right for their animals. Even though Zoorefugio Tarqui is not a government-supported wildlife center, local representatives from the Ministerio del Ambiente (Ecuador's environmental protection government agency) still choose to bring rescued animals to Zoorefugio Tarqui first, knowing they'll receive better care here than many government-subsidized wildlife refuges. This is why William and Fanny are hard at work in the restaurant every single day to put food in the mouths of their three human children as well as over two hundred furry, feathery, and scaly ones in the zoo.

William was raised on this land, and many farms and properties around Tarqui belong to his relatives

What can you do?

Volunteer

No, seriously, you can volunteer. Anyone can volunteer! I'm no biologist, ecologist, or any type of scientist, and you don't have to be one either. All you need is a heart for animals, willingness to get up early and work hard, and a passport. If you want to know more about volunteering at Zoorefugio Tarqui, contact me or send an email to Fanny via the Zoorefugio Tarqui website.

Adopt

While they won't send you a Margay in the mail, you can "adopt" one of the animals at Zoorefugio Tarqui via their website. As I can attest, each and every one of their animals eats like a king, receives superb medical care, and enjoys spacious enclosures that zoo animals in the United States can only dream of. Of course, such great care comes at a price. As mentioned before, Zoorefugio Tarqui is entirely powered by William, Fanny, their kids, and volunteers. When volunteer enrollment drops off, the animals stay just as hungry every day. Those of us with pets in our house know that fifty dollars is a drop in the bucket in terms of annual expenditures for food, toys, vet visits, etc. Yet for that same price you can help feed a Jaguar, a Macaw, or a Tapir for an entire year. Click here to find out more about adopting your own animal from Zoorefugio Tarqui!

The days are long at Zoorefugio Tarqui, but there is still so much more to learn and experience in the Amazon. In the next update, you'll find out what it's like to eat bugs, swim under waterfalls, party in the jungle with natives, and all about life in the rainforest.